Indigenous homelessness, the unseen struggle

A homeless man panhandles for cash on Oullette Street, a busy road in downtown Windsor.

Photographed on Dec. 10, 2021.

Photo by Caleb Coulter/MediaPlex Examiner

By Caleb Coulter and Ravishan Wijemanne

Windsor’s Indigenous population are disproportionately affected by homelessness.

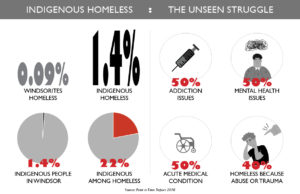

According to this year’s Point-in-Time Count, 22 per cent of Windsor’s homeless were Indigenous People. This statistic is severe considering Indigenous people are only 1.4 per cent of Windsor’s total population. Even on the national scale, Indigenous people are overrepresented among the homeless. According to research by the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, they account for about 28-34 per cent of those in shelters. Yet only about 4 per cent of Canada’s population is Indigenous. Compared to other communal groups, Indigenous People are especially vulnerable. The underlying causes of this crisis need investigating.

Kristen Jeavons, the Indigenous Justice Co-ordinator at Legal Assistance Windsor, said homelessness among Indigenous People is caused by the financial difficulties of COVID-19 compounded by historical trauma.

“Marginalized or vulnerable populations, minorities, they share similar circumstances,” said Jeavons. “Indigenous people have particularly gone through the legal system and social system with such colonial rules and structures imposed. That’s where it makes a difference, how it’s orchestrated by the structures that be.”

A graduate of University of Windsor’s honours criminology program, Jeavons received her Juris Doctor in 2020. She is also a member of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Okmulgee, Oklahoma and is of mixed Cherokee and Creek descent. Her job is where her worlds collided and where she found purpose.

“My work isn’t just a job to me,” said Jeavons. “It’s beyond that. When I take a client’s file, and if I can make a change for that person, for their housing matter or social income matter… overall, the social advocacy part is very dear to my heart. I would like be making more change more and more broadly, city wide or nationally, if I can.”

Founded by the University of Windsor in 1974, Legal Assistance Windsor helps people who cannot afford legal service. Their services also cover those who cannot obtain a legal aid certificate from Legal Aid Ontario, the program overseen by the government of Ontario. LAW was established to provide holistic solutions to Windsor’s underprivileged by using graduates from the university’s many programs. Because of its interdisciplinary staff, LAW offers a variety of programs, helping people who have problems with migration, sexual harassment and human trafficking. They also have social workers to help people with housing.

“When we talk about homelessness, it’s beyond just ‘I couldn’t pay my rent,” said Jeavons. “That might be on paper how it starts… When we look at the whole picture, we find out that they lost their source of income… A client may have an eviction matter, but then we open up another file for social income. We also have an interdisciplinary clinic here for social work… It’s a well of knowledge from all walks of life. We are trying to do everything we can, at the ground level, client file level and even the city council level.”

To address homelessness caused by COVID-19, the City of Windsor has planned to spend an additional $1 million next year. Jeavons said working remotely during the lockdowns made it harder to serve Windsorites suffering from homelessness.

“As an Indigenous person myself, meeting people in person and having that exchange, whether it be the tobacco or protocols that are sacred to us, it’s going to be difficult for a new client come in and build that trust when I haven’t even met them yet,” said Jeavons. “So, the pandemic definitely has put another barrier on that already vulnerable system.”

This year’s number of Indigenous People who are homeless remained unchanged from 2018 according to that year’s Point in Time report. The report says that also suffer from other issues that are complex and intertwined. About half of Windsor’s homeless Indigenous people said they have addiction and or mental health issues. About 40 per cent said their homelessness was caused by trauma or abuse. These complications were also found outside the Indigenous subgroup. In general, more than half of the homeless people who took the survey said they suffered from mental health issues and or violence at home, while about 40 per cent said they had addition issues.

This year’s number of Indigenous People who are homeless remained unchanged from 2018 according to that year’s Point in Time report. The report says that also suffer from other issues that are complex and intertwined. About half of Windsor’s homeless Indigenous people said they have addiction and or mental health issues. About 40 per cent said their homelessness was caused by trauma or abuse. These complications were also found outside the Indigenous subgroup. In general, more than half of the homeless people who took the survey said they suffered from mental health issues and or violence at home, while about 40 per cent said they had addition issues.

Jeavons said these accompanying issues harm the earning potential of these people, limiting them to government welfare programs.

“From the get-go, that kind of income doesn’t allow for much growth beyond minimal necessities,” Jeavons said. “They may be unemployed due to a variety of reasons… Victimization, sexual abuse, physical abuse, mental abuse.”

Homelessness is a problem the City of Windsor has been trying to address for a long time. In 2014, the city launched the Housing and Homelessness Plan, a 10-year programme to ensure every Windsorite has a home. Its priority was to give people immediate access to housing. Thereafter, the program would monitor each case and help people move on to permanent housing. That year, 976 people were served through a federal fund called the Homelessness Partnering Strategy. However, Windsor has had a steady number of people experiencing homelessness since then. The Point in Time report of 2018 was only four people fewer than the report of 2016.

The plan of 2014 identified several reasons for this. At that time, the city’s housing stock was found to be 35-58 years old. Another complication was landlords’ ability to bypass rental increase limitations by creating fresh rental contracts. Although the report did not introduce measures targeting homelessness among Indigenous people, it did highlight the need to increase Aboriginal housing support workers.

An issue that the original plan did not anticipate was Windsor’s sudden population growth. Up to 2016, the growth rate was steady at 2.6 per cent. In 2019, the city reviewed the plan’s progress at midway point. By then, Windsor’s population was projected to grow between 8-11 per cent for the next 15 years. Modest estimates translate that number to about 30,000 newcomers.

Yet, there have been little increase of multiple-dwelling properties to cope with this influx. Only one in four of Windsor’s housing properties are apartment complexes, while more than 60 per cent are single-detached houses. In Essex County, apartments account for a mere 7 per cent while single-detached houses make up more than 80 per cent. Meanwhile, the average price of rent in Windsor and Essex has increased by 36 per cent and 15 per cent, respectively.

According to Jeavons, Indigenous people moving into Windsor find it difficult to secure housing. They could be moving into urban areas to satisfy court orders or conditions put down by child services when they apprehend children. These are short-term migrations from Reserve land in Leamington or the Caldwell Nation. Although systemic measures may mean well, Jeavons said they end up victimizing Indigenous People further by separating their families or forcing them into urban areas like Windsor.

“Indigenous people, because they’ve been harmed by the system, they can shy away from it,” said Jeavons. “I can’t speak for them all, but generally speaking, it’s a level of distrust that’s present.”

Between 2014 and 2019, the city had supported 219 Indigenous people through the Indigenous Advocate. The city’s five-year review of its housing plan found that the majority of Indigenous People suffering from homelessness will “require intensive supports.”

The upshot of the five-year evaluation was the city’s new Housing Master Plan. Not only does this extend the original plan up to 2028, it also re-prioritizes the way the city is to give funding and assistance. The plan commits to a hard measurable goal – creating 100 new affordable housing units specifically for Indigenous People. By 2028, the city plans to reduce homelessness by 80 per cent among Indigenous People.

According to the Housing Master Plan, the prevalence of homelessness among Indigenous People “reflects the legacy of colonialism, intergenerational trauma…and residential schools.”

Jeavons said the Indian Act, the law that determines Indigenous status, is part of that continuing trauma for Indigenous People. Passed in 1876, the law also governs Reserve Land and sets out the Canadian government’s obligations to First Nations. According to Jeavons some of these treaties were made when Indigenous People were not well informed. Therefore, it is questionable whether there was a meeting of minds to form binding contracts.

“It may look like practically making sense, to have the obligations the Canada owes to you, like the duty of care…but ultimately it’s another form of control,” Jeavons said. “I hope in my time that it’s abolished and repealed, but I don’t know. I think to have a piece of legislation that only pertains to one particular group of people is egregious, it’s barbaric.”

Kim Noah, a housing advocate at Can Am Indian Friendship Centre, said she had more in common with her clients than some. The centre is a non-profit organization which helps Indigenous people in Windsor find housing, jobs and self-sufficiency.

Noah, a single mother of four children, was homeless three times in 2015. She had previously lived in a small home for two years but was evicted after she stopped receiving child tax and could no longer afford a home.

“We couch surfed at my mother’s two-bedroom home for a while,” Noah said. “But my mother had addictions that we couldn’t live with.”

Noah and her children stayed with friends for a time, with some of them even paying for Noah and her children to stay in a hotel for several nights. Noah eventually found a home on Pierre Street in Windsor, but soon discovered it was infested with pests.

But Noah’s situation eventually changed for the better. Noah recalled someone telling her to contact Tina Jacobs, a housing advocate at Can-Am Indian Friendship Centre. She got in touch with Jacobs, who provided Noah with a rent subsidy, providing Noah and her family with a safe, pest-free home for the first time in almost a year.

Jacobs offered Noah a permanent position at Can-Am in 2016 as a housing advocate when Jacobs was promoted within the organization. Noah has worked at Can-Am since. Her favourite moments are seeing clients receive a home, sometimes for the first time in years.

“I love when people get housed. Especially people who have been waiting a really long time and have given up,” Noah said.

One of Noah’s clients took two years to house, due to his intimidating appearance, Noah said. People judged this man by his appearance, not realizing he was a very sweet man who when given the chance, not only stayed housed in his unit, but even outgrew the unit and was able to rent a one more suitable for his new needs.

Noah said her dream would be to eventually establish an Indigenous housing shelter in Windsor, as a place to “gain life skills in transitional units”. These skills would not only help Indigenous people to maintain housing when they are able to receive it, but also build a referenceable rental history.

“Just reading bills can be a difficult task for some people. Being able to understand the purpose of paying the full amount within the billing period,” Noah said.

But Noah’s dream of an Indigenous shelter went even further.

“There are women out here that have lost their children to protective services and need skills to be able to bring them home,” said Noah.

These women need to learn and re-learn skills, to get their life back on track. It’s a devastating, traumatic event, losing one’s children. Learning how to make themselves a meal or even just keep up with laundry is so important, said Noah.

Noah believes her shelter could provide Indigenous people a place to experience healing.

“Normally, when Indigenous women have their children taken from them, they have lost their housing too. If they don’t have their children anymore, they won’t have their benefits,” said Noah.

“Reach out for support. You can fight back against evictions, there are options for you. There are many reasons why people become homeless, reaching out is the first step.”

To individuals wanting to help the Can-Am Indian Friendship Centre, Noah said to call the centre.

“Start the conversation with peers. Get it out there that some people are homeless, there are different reasons why people become homeless. Take the shame out of homelessness,” said Noah.

The City of Windsor’s Housing and Children’s Services has worked towards helping homeless Indigenous in Windsor.

Kelly Goz, the Manager of Homelessness and Housing Support, said while she is a settler and cannot always provide context on all Indigenous issues, her department keeps a “point in time count” for homeless Indigenous people.

“Historically, Indigenous peoples are overrepresented in homelessness,” Goz said.

Goz’s department has developed a 10-year housing and homelessness master plan for Windsor, which addressed Indigenous homelessness specifically.

“Housing Services has a good working relationship with our Indigenous providers,” Goz said. “In addition, we have continued to work to increase awareness and education on the truth of Indigenous peoples by Indigenous peoples.”

The housing and homelessness master plan contains seven key goals, culminating in a vision of Windsor as “an inclusive community where everyone has a safe, affordable, accessible and quality home and everyone lives where they can actively participate,” said the official document on the City of Windsor’s website.

The goals were put in place in 2019 and are planned to continue until 2028. The goals are:

- Sustain and expand the social and affordable housing supply.

- Sustain and expand housing linked with supports.

- Ending homelessness.

- Address Indigenous housing and homelessness needs.

- Reduce and prevent youth homelessness.

- Foster successful tenancies through community collaboration.

- Monitor, report and evaluate.

Key targets of the plan include:

30 per cent more affordable and/or rent-assisted units by 2028

On average, 30 per cent of existing units will be repaired annually

By 2024, 70 more people will be housed through the Housing First Program

By 2024, 50 per cent of people experiencing chronic homelessness will be housed

By 2028, 100 per cent of people experiencing chronic and episodic homelessness will be housed

If this is achieved as planned, what would Windsor look like with Indigenous people fully supported and integrated into the city?

What would a 0 per cent homeless Windsor look like? Would this be a step in the right direction in reconciliation with Indigenous people?

The City of Windsor may plan to hire a third Indigenous housing support worker, according to CBC News Windsor.

Jeavons said, “I think when it comes down to homelessness, nothing else matters if you don’t have a home to go to, a pillow to put your head on, nothing else matters. That’s ground zero.”

SIDEBAR

Did you know?

The Indian Act as it is known now was created in 1876. Several iterations in 1763 (The Royal Proclamation), 1850 (Act for the better protection of the Lands and Property of the Indians in Lower Canada), 1857 (Gradual Civilization Act) and 1869 (Enfranchisement Act) contributed to the final document’s creation.

Indigenous Festival Bans

Near the turn of the 20th century, the Indian Act banned many Indigenous celebrations such as the Potlach, Sundance and Powwow.

These bans were not lifted until 1951, when the Act was amended.

Residential Schools

Residential schools in Canada existed from 1831, when the first residential school was opened in Brantford, Ontario, to 1996, when the last residential school was closed in Punnichy, Saskatchewan.

At least 4,118 children died in residential schools in Canada. These deaths were only those recorded, however, with recent discoveries in British Columbia suggesting a higher death toll.

At least 150,000 First Nations, Metis and Inuit children attended residential schools in Canada.