Lifesaving Sport: the world’s only humanitarian sport

By Rylee Livingston

The official, arm raised, dressed in a white collared shirt, whistles the competitors up onto the blocks.

“Take your marks,” a robotic voice says from the starting box.

The fiberglass fins make a definitive slap against the starting blocks as the athletes dive into the pool and start the race.

The lifesaving sport competition gets underway.

More than just regular swimming, lifesaving sport incorporates aspects of lifeguarding and lifesaving into a fast-paced competition.

Peyton Hodges is a 12-year-old lifesaving sport athlete.

“My favourite event is obstacle swim because my favourite stroke is freestyle and the obstacle part just adds a little bit of challenge to it,” said Hodges. “So you just get to go under and over and race as fast as you can.”

This sport – which many do not even know exists – is having continued success in Canada and around the world, with renewed interest in our area. But the question is, what is lifesaving sport?

What is Lifesaving Sport?

According to the Lifesaving Society website, “Lifesaving sport is the only sport whose skills are first learned for humanitarian purposes.”

Shanna Reid is a lifesaving official, coach and athlete with more than two decades of experience in the sport. She finds it difficult to easily explain to people what the sport is all about.

“What do I tell them first, right?” said Reid. “I tend to focus on, no, it’s not lifeguarding, it’s not first aid. Because that’s what comes to their mind first. So, I try to focus on where we’re swimming in the pool. We’re going fast. We’re using equipment. It’s elements that are indicative of saving a person, but going fast.”

Over the years, Reid has come up with what she calls an “elevator pitch” to help quickly explain the sport.

“It’s like you’re going from the ground floor to the 150th floor,” said Reid. “But I tried to pare it down to the point where you kind of get most of the elements.”

The connection to saving lives is apparent in each race that these swimmers are in, says Reid in her pitch.

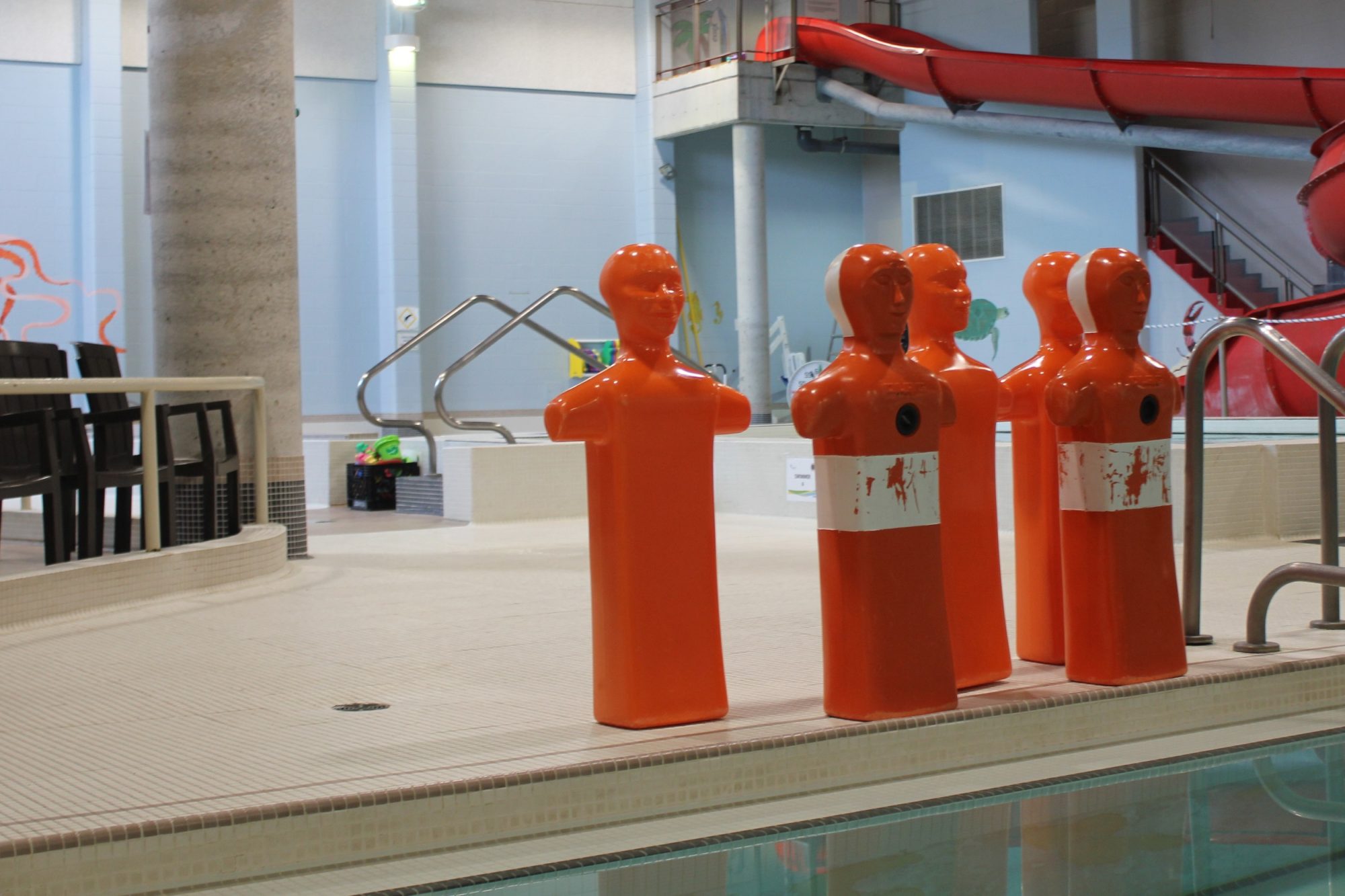

“The use of mannequins to simulate victims, the use of gates to simulate the need to recover a body from the bottom, the use of fins as a speed rescue aid, the use of a rescue tube to assist with manikin pick up and recovery are a few of the added pieces of equipment to add to the excitement of the speed of each event,” Reid writes.

The sport was originally designed to help keep lifeguards and lifesavers in good physical shape while giving them an opportunity to practice their skills. This continues to be the case, with the majority of athletes actively working as lifeguards in pools and on waterfronts across the country.

Lifesaving sport has a wide variety of events – from pool events, surf events (taking place in open water like lakes and oceans) and Simulated Emergency Response Competition (SERC) involving dry-land and in-water simulated first aid and rescue scenarios.

Recognized by the International Olympic Committee and the Commonwealth Games Federation, the sport is governed by the Lifesaving Society in Canada. However, the sport is also recognized across the world, governed by the International Life Saving Federation. The sport is incredibly popular in Australia, New Zealand, England, Wales, Northern Ireland, India, the Caribbean and other countries.

In Ontario, the sport is popular in the Greater Toronto Area, but it has been gaining traction in Windsor-Essex. The Windsor International Aquatic and Training Centre has hosted both national and international lifesaving competitions: the Canadian Pool Lifesaving Championships in June 2023 and the Commonwealth Lifesaving Championships in September 2023. Windsor-Essex is also host to a brand-new team – the Essex Swim and Lifesaving Club, developing athletes from across the region. Essex will be hosting the Ontario Lifeguard Championships in February of 2024.

- Peyton Hodges waits for direction from her coach during the Markham Lifesaving Invitational at the Markham Pan-Am Centre in Markham, ON on Nov. 25, 2023. Photo by Rylee Livingston

- Peyton Hodges swim warm-ups during the Markham Lifesaving Invitational at the Markham Pan-Am Centre on Nov. 25, 2023. Hodges is a junior member of the Essex Swim and Lifesaving Club. Photo by Rylee Livingston

- Peyton Hodges throws a rope to Owen Williams during the 10 metre line throw event at the Markham Lifesaving Invitational on Nov. 25, 2023. Photo by Rylee Livingston.

- Swimming fins and shoes litter the pool deck during the Junior Markham Lifesaving Invitational at the Markham Pan Am Centre in Markham, ON on Nov. 25, 2023. Photo by Rylee Livingston.

- Peyton Hodges smiles at her coach as she warms-up before the Markham Lifesaving Invitational on Nov. 25, 2023. Photo by Rylee Livingston.

- Peyton Hodges poses for a photo before competing in the Markham Lifesaving Invitational at the Markham Pan Am Centre on Nov. 25, 2023. Photo by Rylee Livingston.

- Lifesaving sport manikins wait to be used during Essex Swim and Lifesaving Club practice at the Essex Recreation Complex on Nov. 26, 2023. Photo by Rylee Livingston.

- A lifesaving sport athlete competes on a surf ski at Surf World Championships. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- Shanna Reid and Sarah Ingleton celebrate their wins at the Markham Pan Am Centre. Photo coutesy of Shanna Reid.

- Shanna Reid and Cynthia Cakebread officiate at a lifesaving sport surf competition. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- A photo of surf skis in storage. Equipment such as this is used in lifesaving sport surf competition. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- Canadian athletes competing in the board rescue event at Surf Lifesaving World Championships. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- Shanna Reid officiates at a lifesaving sport surf competition. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- Coach Shanna Reid poses with her Saugeen Shores Lifesaving Club Athletes celebrating their second place win at SERC in 2016.

- Saugeen Shores Lifesaving Club athletes pose with surf skis during training. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- An athlete trains for lifesaving sport surf competition. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- Lorraine Wilson-Saliba and Shanna Reid officiate at provincial waterfront competition. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- Shanna Reid officiates at Surf National Competition in Quebec. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- The Saugeen Shores Lifesaving Club junior team warms up before competition at the Markham Lifesaving Invitational on Nov. 25, 2023. Photo by Rylee Livingston.

- Shanna Reid and her partner celebrate their win of a silver medal in the line throw event at World Championships. Photo courtesy of Shanna Reid.

- Shanna Reid and Sarah Ingleton train together as masters athletes for the Saugeen Shores Lifesaving Club. Photo coutesy of Shanna Reid.

- Shanna Reid and Sarah Ingleton train together as masters athletes for the Saugeen Shores Lifesaving Club. Photo coutesy of Shanna Reid.

- Peyton Hodges (12), Brooklyn Carson (9) and Andrezj Winarski (11) prepare to swim warm-ups during the Markham Lifesaving Invitational at the Markham Pan Am Centre in Markham, ON on Nov. 25, 2023. All three are athletes on the junior team of the Essex Swim and Lifesaving Club. Photo by Rylee Livingston

The Athletes

Athletes have the opportunity to showcase their skills in local, regional, provincial, national and international competitions. The sport is so small that there are no qualifiers for provincial or national competitions, but international competitions require athletes to be chosen for the Canadian National Team.

National team coaches attend Canadian Pool Lifesaving Championships to scout potential national athletes from across the country. These athletes are chosen and announced at the end of the competition during an awards banquet. They train with their individual clubs and come together with their national coaches to prepare for international competition, such as the Commonwealth Championships and World Championships.

In Canada, athletes typically compete at three different divisions – junior, senior and masters. Juniors from 7-16 years old with necessary swimming skills begin with the Lifesaving Sport Fundamentals program. Juniors from any age can graduate from the Fundamentals program and compete in their respective age groups. Seniors are age 15 and older – they must be registered athletes and have their minimum qualifications of the Bronze Medallion program. The masters division is for athletes 30-plus who are still wanting to compete in the sport.

Ian Yurikh is a 24-year-old lifesaving athlete originally from Markham, ON. He is now a member of the newly-formed Essex Swim and Lifesaving Club (ESLC), operating out of the Essex Recreation Complex.

“The sport is very unique in that not a lot of people have heard about it,” said Yurikh. “It’s like swimming, but there are obstacles thrown in there, mannequins you’ve got to carry, ropes you’ve got to throw. I got bored of strictly chasing walls a long time ago, when it came to just swimming.”

Hodges competes on the junior ESLC team. She is passionate about the sport and loves competing as a team.

“It’s really fun,” said Hodges. “I get to make new friends and just go to competitions and compete against people and show my skills.”

With a shortage of lifeguards both locally and nationally, lifesaving sport not only helps to introduce swimmers to lifesaving but helps to retain lifeguards in the lifesaving world.

“There’s more than one way to put lifeguards on the deck,” said Reid. “One of the ways is to pull in those athletes that are already swimming and getting them certified.”

Another way is to introduce already-certified lifeguards – or those who are currently becoming lifeguards – to lifesaving sport.

“I was going up through the Learn to Swim (program) and I went through my Bronze Medallion and then I did my Bronze Cross,” said Reid. “And then somebody tapped me on the shoulder and said, ‘Well, why don’t you keep going?’ Okay, I’ll keep going.”

Reid developed the Saugeen Shores Lifesaving Team in 2007 through both of these methods. She tapped into the local swim team, recruiting 12 to 17-year-olds by certifying them in a weekend.

“Right away, they were like, ‘Oh, we didn’t know we could do this,’” said Reid. “Nobody asked them before. And so I got some of my best staff coming out of that… Five of them got on national teams, because they were good swimmers.”

Reid thinks local clubs should be “tapping people on the shoulder” to encourage them not only to join lifesaving but also to become lifeguards.

“I don’t think we do enough of that,” said Reid.

Why compete in Lifesaving?

For Reid and many others, lifesaving sport is about coming together.

“Well, it’s really about camaraderie,” said Reid. “There’s no other sport like this. Swimming is very insular. You have your team and they ‘Rah, rah, rah,’ you. And that’s great. But you get up on the blocks, and you’re by yourself. This sport is not like that at all.”

In many sports, your competition becomes your enemy, said Reid. This is not the case in lifesaving, where it can be about “learning on the line.”

“I remember my first masters in Italy,” said Reid. “I’m standing on the line, and the waves were just huge. We were doing the paddleboard event. And I’m standing beside an Australian over here, and probably a Kiwi over here. And I’m like, ‘How do you get through those big waves?’ And they’re like, ‘Oh, well, this is what you do. You’re hanging on and you paddle, paddle, paddle. And then when the waves break in, you do a little duck dive.’ And I’m like, ‘A duck dive. What’s that?’”

Officials and athletes alike support each other and rally together for what the sport is all about: lifesaving.

“That’s the core of lifesaving sport. And we’ve seen in competitions, where it’s that humanitarianism that comes out big time,” said Reid. “We were in Ontario, one year, with great, big, huge waves. We were doing the swimming event, and somebody was in trouble. Well, the person that was in first stopped, grabbed them and brought them back to the line. We couldn’t redo the event. But he sacrificed for the saving.”

For others, it’s about the teamwork and athleticism.

“A lot of people really put a lot of emphasis on the lifesaving part of it and the lifeguarding part of it,” said Yurikh. “For me, personally, I more so take it as an opportunity to stay fit and have a team to do it with.”

For Hodges, it’s about continuing to swim when she is too old for regular swimming lessons but too young to become a lifeguard.

“It’s a really nice experience,” said Hodges. “Because I not only get to work on my endurance and technique and strokes, but I can work on my lifesaving skills.

Hodges wants more people to experience the sport.

“I encourage people to do this,” said Hodges. “It’s really fun. It will make you a stronger swimmer.”

For more information about the sport, volunteering, competitions and more, visit www.lifesavingsociety.com/lifesaving-sport or www.ilsf.org/lifesaving-sport. To become involved locally, contact Essex Swim and Lifesaving Club coach Zak Kolasa by email at [email protected].

For many lifesaving athletes, coaches and officials, once they’re in, they don’t want to leave.

“I’ll continue as long as I can swim,” said Yurikh. “Yeah, I’ll continue. As long as there’s an accessible pool and an accessible team. Of course, why not?”

Reid shares a similar sentiment, having been “hooked” since she started in 2000.

“I’m in it for life,” said Reid. “I see some of these old Australian officials that keep coming back year after year, and they keep putting them in positions where they don’t have to walk. But they’re there because of the comradery. And I’m like, ‘Oh I don’t want to get there.’ But I’m going to get there!”